Edgar Payne Composition Of Outdoor Painting

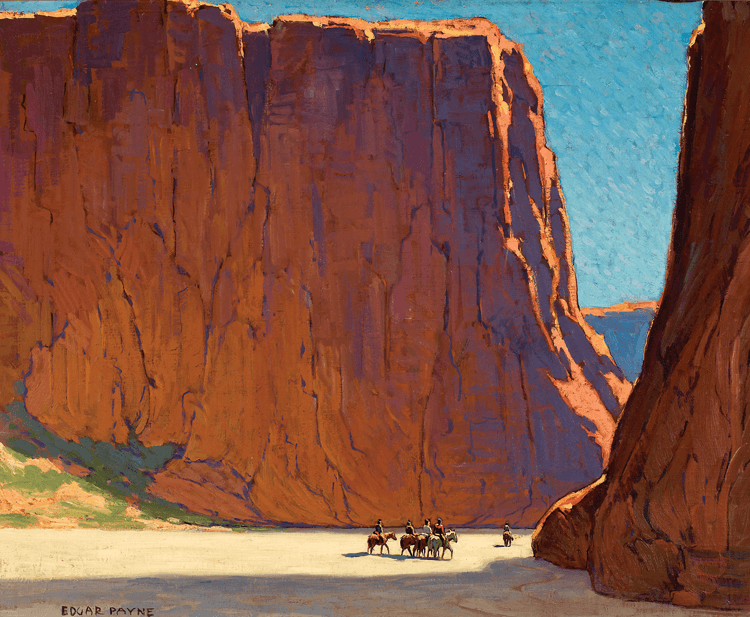

Edgar Payne Digital Painting Study of 'Cole Canyon (Arizona)' by Mary Highstreet

Find many great new & used options and get the best deals for Composition of Outdoor Painting by Edgar Payne (2005, Hardcover) at the best online prices at eBay! Free shipping for many products! This item: Composition of Outdoor Painting by Edgar Payne Hardcover $49.95. Sold by ExtraMile and ships from Amazon Fulfillment. Carlson's Guide to Landscape Painting by John F. Carlson Paperback $11.99. Ships from and sold by Amazon.com. Composition of Outdoor Painting by Edgar Payne This is a well-loved book. It is a great a compilation of different compositional designs and as it relates to the landscape. However all of the concepts can be applied to still life and portraiture. I have read through the book multiple times.

'Composition of Outdoor Painting' by Edgar Payne

Edgar Payne Composition Of Outdoor Painting Pdf

(pp. 105-170)

In Chapter 3, Edgar Payne goes over the details of good composition and gives examples of 15 different types of composition. The conclusion gives us some final thoughts on the most important concepts for students to remember. Payne also highlights some of the pitfalls typically encountered and provides encouragement on how to overcome them. The addenda was written by Edgar Payne's daughter, Evelyn Payne Hatcher; here she gives invaluable knowledge of things Payne meant to share about his methods as well as the observations she made of her parents techniques from her perspective. She shares meaningful art knowledge imparted to her by both her father, Edgar, and mother (also an artist), Elsie.

. . .

Summary of Main Points:

1. Payne lists 15 principal forms/stems of composition: Steelyard, The Balance Scale, Circle, S or Compound Curve, Pyramid, The Cross, The Radiating Line, Ell or Rectangular, Suspended Steelyard, Three Spot, Grouped Mass, Diagonal Line, The Tunnel, The Silhouette, The Pattern.

a. When placing the main masses, consider all three dimensions, one can be farther back in perspective; utilize the foreground, middle ground, and background when placing masses.

g. Be aware that if the lines in the Radiation Composition are not unbroken it forces the eye to travel too fast (as in an obvious spoke like design); to solve this issue make sure all lines are broken, irregular, or intercepted.

p. 'The first and last thing [for the painter] to consider is the instinctive feeling for balance. The more this can be exercised, the more pleasing will be the harmony.' (p. 127)

g. Be aware that if the lines in the Radiation Composition are not unbroken it forces the eye to travel too fast (as in an obvious spoke like design); to solve this issue make sure all lines are broken, irregular, or intercepted.

p. 'The first and last thing [for the painter] to consider is the instinctive feeling for balance. The more this can be exercised, the more pleasing will be the harmony.' (p. 127)

2. 'It is not the size or the number of paintings but the degree of ability that counts.' (p. 135)

2. These are necessary the requirements for the student: to respect natural laws, truths, principals, tradition and precedent, as well as to have the qualities of perseverance, determination to achieve, and enthusiasm in study and depiction.

2. Unity is be made possible by an observance of principals that create it, thus a knowledge of fundamentals is key.

2. Mistakes are part of the profession, and shouldn't discourage. 'The art of painting is a matter of seeing mistakes, overcoming obstacles and keeping fundamental principals always at hand.' (p. 138)

3. Evelyn Payne Hatcher writes of her parents: '...it was the process, the learning, even the struggle that was to them more important than the product.' (p. 142)

3. 'Plein aire painters seldom paint larger works in the field, because the light often changes too rapidly. Sometimes as in early morning and near sundown, very rapidly indeed.' (p. 144)

3. 'The underlying principal of [Payne's] approach to color, and to art in general, is the balance of vitality (contrast and opposition) with harmony.' (p. 154)

. . .

More Details:

Composition Of Outdoor Painting Pdf

Edgar Payne Book

1. Types of Composition

The underdrawing of compositional foundation lines in the preliminary stages of a painting can be directly compared to a wire armature in sculpture. The structure is essential and necessary, but also important is to disguise it skillfully so as not to make it obvious. 'The dominant aim of the student should be to train and equip himself to the point where he can judge unity and all of its contributing factors by 'feeling.' (p. 105) 'The more thought and concentration put into his preparation, the easier will be the procedure and the finer the design.' (p.106) Unity is achieved on the basis of principles, whether intuitive or studied. Executing a multitude of pen and ink studies on composition in various well established painters artworks are a valuable activity in the education of the student. Payne lists 15 principal forms/stems of composition: Steelyard, The Balance Scale, Circle, S or Compound Curve, Pyramid, The Cross, The Radiating Line, Ell or Rectangular, Suspended Steelyard, Three Spot, Grouped Mass, Diagonal Line, The Tunnel, The Silhouette, The Pattern. No one approach is more valuable than another, the importance is placed on careful study and practice of all compositional formulas. Equally valuable is to try composition naturally and intuitively, without any specific principal.

a. Steelyard

The most popular form of compositional balance used. A scale with two unequal sized masses, the fulcrum placed toward the larger one. The focal point should be on or near the fulcrum or main weight. There is usually a vertical visual connection between the main and lesser weights. When placing the weights, consider all three dimensions, one can be farther back in perspective; utilize the foreground, middle ground, and background when placing masses.

b. The Balance Scale

Most used for mountain compositions where the peak reaches near the top center. Also useful in the decorative style: for wall decorations, or murals.

c. Circle

Akin to the steelyard in popularity, the circle or O composition. It should be roughly indicated, not obvious; as such, it can be a rough circle, also taking on the appearance of a rectangular or irregular opening. The U shape is also a visible influence; suggested by a lateral ground plane and two vertical planes.

d. S or Compound Curve

Typically suggested by a line or edge, rather than a mass; for example a river or road. It can also be seen when a general curved suggestion is formed, in both positive and negative spaces, anywhere in the composition. If a POI (point of interest) exists, it should be placed on or near the converging end of the main lines.

e. Pyramid

The structure of the pyramid or triangle composition aids in stability and permanence. This can be created by a line, a mass, or sprinklings of various interests.

f. The Cross

Not as useful for outdoor compositions, the cross is better used in works with architecture, boats, or leafless trees. The POI should be placed near the crossing of main lines.

g. The Radiating Line

This composition draws attention to the POI, which should be placed at or near the converging line. Be aware that if the lines are not unbroken it forces the eye to travel too fast (as in an obvious spoke like design); to solve this issue make sure all lines are broken, irregular, or intercepted.

h. Ell or Rectangular

This L shaped composition is similar to, and compatible with, the steelyard. It is not very common as it is tough to balance a large vertical mass with one horizontal line.

i. Suspended Steelyard

An upside down version of the steelyard, where masses are placed high on the canvas and the foreground is simple. The same principals of unequal measures and focal point as in the steelyard composition can be applied here.

j. Three Spot

This can be it's own composition or it can work within other types of compositions, such as the steelyard or pyramid. Two masses don't create unity as well as three do. Three is only the minimum, you can add more spots to aid in balance and unification.

k. Grouped Mass

Unity is achieved here by placing several masses into a group. This is the most widely used in painting the still life. It is easily and best combined with pattern and silhouette compositions.

l. Diagonal Line

Once creating a considerable slant in the main line (either from top left to bottom right or reversed), the next important factor is to oppose or intercept these by other lines or masses. The are below the main line is generally either painted in a unification of dark values only or light values only, and the opposite value above the main line.

m. The Tunnel

Similar to the circle, the tunnel differs in that it is dependent on the third dimension in perspective lines and planes. There is generally seen in an opening with depth, as seen under a bridge or through a break in trees.

n. The Silhouette

This reduced interest and contrast to one mass where contour is more prominent. Interchange, the placement of dark on light values or vice verse to create a contrasting edge, adds interest here. The masses should have their values simplified or brought close together to indicate a strong silhouette.

o. The Pattern

The most abstract principal, which depends entirely on a feeling for unity. It is beneficial for experimentation and study because it discourages reliance on principals and tests one's natural compositional abilities. 'It's dependence is mainly on imagination or ingenuity or an instinctive feeling for harmony when it appears in nature.' (126) Here the patterns may be arranged with or without a POI.

p. End Notes

'The first and last thing [for the painter] to consider is the instinctive feeling for balance. The more this can be exercised, the more pleasing will be the harmony.' (p. 127) The overall thing to keep in mind when composition is our own personal taste and judgement. Principal compositional designs do play an important part in selection, rejection, and composition. If we rely too heavily on compositional stems or designs in our picture, we risk will loose some originality and quality. These ideas are the tools that will hopefully lead us to develop a reliance on a more intuitive sense of taste and feeling for balance in the end. The enjoyment of composition, and study there of, is an essential first step that will allow us to understanding how to arrive at our own good compositions.

2. Conclusion

'A main objective in the art of painting is to disguise, [as much] as possible, the use of methods or the influence of principals.' (p. 129) 'Underlying all fine art are sound principals...[which] cannot be reiterated too often.' (p. 129) New ideas are important but also is a knowledge of foundational principals. A new idea may either make or break a painting; the question we need to ask is: does this new idea it strengthen or weaken the composition? Mistakes are part of the profession, and shouldn't discourage. 'The art of painting is a matter of seeing mistakes, overcoming obstacles and keeping fundamental principals always at hand.' (p. 138) 'The quality achieved in any work must, in the last analysis, depend on the ideas and efforts of the student himself and the goal he has set. He is the master of his own destiny as far as accomplishment in art is concerned.' (p. 130) 'Learning the art of painting is not an easy task. It takes a great deal of intelligence, keen analysis, study and practice.' (p. 130) All principals gleaned and used as means of achieving artistic quality are united for one purpose only: to bring unity and harmony to the composition. The first consideration for the beginner is to develop ones natural talents; then is the enjoyment of the process; and lastly, the final goal/purpose of art is for the benefit of humanity in general. Developing ones own style is essential before making any kind of artistic impact in the world. The purpose of art knowledge and principals is to aid the imagination to better and more easily translate the world around us.

Problems arise from two main causes: errors made in the concept or mistakes made in drawing or painting. Other reasons good design and results are hindered could include the artist may not be in the right mindset, or not have the energy being tired or sick, or even the employment of over-concentration all of which can cause poor judgement. The solution is solitary: focus your mind on something else entirely different from art for a time. Good work is dependent on proper circumstances. '[The] overly ambitious [must learn]...art cannot be forced, but comes naturally and easily only when the right conditions exist[;] enjoyment in painting should never be overwhelmed by ambition. Ambition should be directed more toward developing the artistic faculties than the outward production of pictures.' (p. 135) 'It is not the size or the number of paintings but the degree of ability that counts.' (p. 135)

Hard work, study, analysis, and research must be done first before pleasure can be fully and completely derived from painting. These are necessary the requirements for the student: to respect natural laws, truths, principals, tradition and precedent, as well as to have the qualities of perseverance, determination to achieve, and enthusiasm in study and depiction. There a freedom and originality within the flexibility of the principals. One path leading to individual artistic expression includes the employment of individuality in thought, a respect for nature, and established truths and principals. Unity is made possible by an observance of principals that create it, thus a knowledge of fundamentals is key. 'Most of the problems in painting can be solved and originality achieved when we have a broad knowledge and respect for the purpose and importance of principals.' (p. 137)

'Whenever we see a fine painting we thoroughly appreciate the accomplishment of the artist. We admire his wisdom in selection and concept; his skill and ingenuity in execution. We know that genius, ability, perseverance and determination have contributed toward his artistic success - that he only succeeded by and endless study of fundamentals and by continually staying with each problem until it was mastered.' (p. 137)

Learning to coordinate and balance head knowledge with practical physical and intuitive knowledge takes manual practice and application. 'The first and last important matter in the study and practice of art is knowledge.' (p. 139)

3. Addenda

Evelyn Payne Hatcher writes of her parents: '...it was the process, the learning, even the struggle that was to them more important than the product.' (p. 142) Payne considered color studies made in the field to be for personal use only, he never signed or sold them as a rule. Two things were observed by Payne's sketches: they were either a study of forms, or of how to make pleasing compositional arrangements. Payne kept a small notebook in his kit as well as in his pocket along with a 6B pencil.

'Plein aire painters seldom paint larger works in the field, because the light often changes too rapidly. Sometimes as in early morning and near sundown, very rapidly indeed.' (p. 144) Some suggest that Payne's oil sketches were completed in less than half an hour. When Payne mentioned wisdom in the development of knowledge in this book, he most likely often means the practical and physical knowledge learned through experience with painting and sketching, not just head knowledge and study of books. '[Payne] planned compositions with pencil drawings and so was able to paint rapidly at the easel without laboring over layout.' (p. 146) 'Both [Evelyn's] parents insisted that practice in drawing from nature teaches one to really see, which is rewarding in itself.' (p. 146)

When Payne worked he often employed the following procedure:

1. Once he decided on the main subjects, the then tried out various compositions. In the field Payne would sometimes use a viewfinder (a rectangle cut out of cardboard) to help visualize the composition.

2. Next (whether executed in the field or the studio), 'was to draw the scene on canvas with charcoal, sometimes sketchy and sometimes in detail, depending on the subject, with indications of darker areas.' (p. 147)

3. Then he '...establish[ed] the pattern of darks and lights (values) by painting a wash or stain (often thin red ochre) over the dark or shadowed areas.' (p. 149)

4. Next, 'working all over the canvas, he used thin paint to establish the color scheme.' (p. 149)

5. '...thicker pigment was applied to the dark areas in hues that would be appropriate for the shadows...' (p. 149)

6. Applying heavier paint, he gave attention to the solidity of forms, 'modeling[.]' He worked to some extent from dark to light, as in traditional oil painting, but also tended to work all over the canvas to maintain the relationships between dark and light, warm and cool, in accordance with the color scheme he had in mind, leaving only the highlights for last.' (p. 149)

He worked in a similar manner with color studies in tempera, the differences being he started with a wash of color (or colored paper) and dabbed the paint on, leaving the background showing in some areas to produce vibrance. Payne laid out the darks and lights in a composition as he was drawing it, and thought first this way, beginners typically think in terms of local color first. A dividing of the picture plane in thirds is also a pleasing composition where focal points rest on the devision lines. 'The underlying principal of [Payne's] approach to color, and to art in general, is the balance of vitality (contrast and opposition) with harmony.' (p. 154) A principal which was discussed in the latter half of Chapter 2.

In the color section, Evelyn goes into detail explaining basic color theory, as well as giving a few examples of practical methods of execution for learning it such as a times table of paint mixing, and the 'soup' method.

The underdrawing of compositional foundation lines in the preliminary stages of a painting can be directly compared to a wire armature in sculpture. The structure is essential and necessary, but also important is to disguise it skillfully so as not to make it obvious. 'The dominant aim of the student should be to train and equip himself to the point where he can judge unity and all of its contributing factors by 'feeling.' (p. 105) 'The more thought and concentration put into his preparation, the easier will be the procedure and the finer the design.' (p.106) Unity is achieved on the basis of principles, whether intuitive or studied. Executing a multitude of pen and ink studies on composition in various well established painters artworks are a valuable activity in the education of the student. Payne lists 15 principal forms/stems of composition: Steelyard, The Balance Scale, Circle, S or Compound Curve, Pyramid, The Cross, The Radiating Line, Ell or Rectangular, Suspended Steelyard, Three Spot, Grouped Mass, Diagonal Line, The Tunnel, The Silhouette, The Pattern. No one approach is more valuable than another, the importance is placed on careful study and practice of all compositional formulas. Equally valuable is to try composition naturally and intuitively, without any specific principal.

a. Steelyard

The most popular form of compositional balance used. A scale with two unequal sized masses, the fulcrum placed toward the larger one. The focal point should be on or near the fulcrum or main weight. There is usually a vertical visual connection between the main and lesser weights. When placing the weights, consider all three dimensions, one can be farther back in perspective; utilize the foreground, middle ground, and background when placing masses.

b. The Balance Scale

Most used for mountain compositions where the peak reaches near the top center. Also useful in the decorative style: for wall decorations, or murals.

c. Circle

Akin to the steelyard in popularity, the circle or O composition. It should be roughly indicated, not obvious; as such, it can be a rough circle, also taking on the appearance of a rectangular or irregular opening. The U shape is also a visible influence; suggested by a lateral ground plane and two vertical planes.

d. S or Compound Curve

Typically suggested by a line or edge, rather than a mass; for example a river or road. It can also be seen when a general curved suggestion is formed, in both positive and negative spaces, anywhere in the composition. If a POI (point of interest) exists, it should be placed on or near the converging end of the main lines.

e. Pyramid

The structure of the pyramid or triangle composition aids in stability and permanence. This can be created by a line, a mass, or sprinklings of various interests.

f. The Cross

Not as useful for outdoor compositions, the cross is better used in works with architecture, boats, or leafless trees. The POI should be placed near the crossing of main lines.

g. The Radiating Line

This composition draws attention to the POI, which should be placed at or near the converging line. Be aware that if the lines are not unbroken it forces the eye to travel too fast (as in an obvious spoke like design); to solve this issue make sure all lines are broken, irregular, or intercepted.

h. Ell or Rectangular

This L shaped composition is similar to, and compatible with, the steelyard. It is not very common as it is tough to balance a large vertical mass with one horizontal line.

i. Suspended Steelyard

An upside down version of the steelyard, where masses are placed high on the canvas and the foreground is simple. The same principals of unequal measures and focal point as in the steelyard composition can be applied here.

j. Three Spot

This can be it's own composition or it can work within other types of compositions, such as the steelyard or pyramid. Two masses don't create unity as well as three do. Three is only the minimum, you can add more spots to aid in balance and unification.

k. Grouped Mass

Unity is achieved here by placing several masses into a group. This is the most widely used in painting the still life. It is easily and best combined with pattern and silhouette compositions.

l. Diagonal Line

Once creating a considerable slant in the main line (either from top left to bottom right or reversed), the next important factor is to oppose or intercept these by other lines or masses. The are below the main line is generally either painted in a unification of dark values only or light values only, and the opposite value above the main line.

m. The Tunnel

Similar to the circle, the tunnel differs in that it is dependent on the third dimension in perspective lines and planes. There is generally seen in an opening with depth, as seen under a bridge or through a break in trees.

n. The Silhouette

This reduced interest and contrast to one mass where contour is more prominent. Interchange, the placement of dark on light values or vice verse to create a contrasting edge, adds interest here. The masses should have their values simplified or brought close together to indicate a strong silhouette.

o. The Pattern

The most abstract principal, which depends entirely on a feeling for unity. It is beneficial for experimentation and study because it discourages reliance on principals and tests one's natural compositional abilities. 'It's dependence is mainly on imagination or ingenuity or an instinctive feeling for harmony when it appears in nature.' (126) Here the patterns may be arranged with or without a POI.

p. End Notes

'The first and last thing [for the painter] to consider is the instinctive feeling for balance. The more this can be exercised, the more pleasing will be the harmony.' (p. 127) The overall thing to keep in mind when composition is our own personal taste and judgement. Principal compositional designs do play an important part in selection, rejection, and composition. If we rely too heavily on compositional stems or designs in our picture, we risk will loose some originality and quality. These ideas are the tools that will hopefully lead us to develop a reliance on a more intuitive sense of taste and feeling for balance in the end. The enjoyment of composition, and study there of, is an essential first step that will allow us to understanding how to arrive at our own good compositions.

2. Conclusion

'A main objective in the art of painting is to disguise, [as much] as possible, the use of methods or the influence of principals.' (p. 129) 'Underlying all fine art are sound principals...[which] cannot be reiterated too often.' (p. 129) New ideas are important but also is a knowledge of foundational principals. A new idea may either make or break a painting; the question we need to ask is: does this new idea it strengthen or weaken the composition? Mistakes are part of the profession, and shouldn't discourage. 'The art of painting is a matter of seeing mistakes, overcoming obstacles and keeping fundamental principals always at hand.' (p. 138) 'The quality achieved in any work must, in the last analysis, depend on the ideas and efforts of the student himself and the goal he has set. He is the master of his own destiny as far as accomplishment in art is concerned.' (p. 130) 'Learning the art of painting is not an easy task. It takes a great deal of intelligence, keen analysis, study and practice.' (p. 130) All principals gleaned and used as means of achieving artistic quality are united for one purpose only: to bring unity and harmony to the composition. The first consideration for the beginner is to develop ones natural talents; then is the enjoyment of the process; and lastly, the final goal/purpose of art is for the benefit of humanity in general. Developing ones own style is essential before making any kind of artistic impact in the world. The purpose of art knowledge and principals is to aid the imagination to better and more easily translate the world around us.

Problems arise from two main causes: errors made in the concept or mistakes made in drawing or painting. Other reasons good design and results are hindered could include the artist may not be in the right mindset, or not have the energy being tired or sick, or even the employment of over-concentration all of which can cause poor judgement. The solution is solitary: focus your mind on something else entirely different from art for a time. Good work is dependent on proper circumstances. '[The] overly ambitious [must learn]...art cannot be forced, but comes naturally and easily only when the right conditions exist[;] enjoyment in painting should never be overwhelmed by ambition. Ambition should be directed more toward developing the artistic faculties than the outward production of pictures.' (p. 135) 'It is not the size or the number of paintings but the degree of ability that counts.' (p. 135)

Hard work, study, analysis, and research must be done first before pleasure can be fully and completely derived from painting. These are necessary the requirements for the student: to respect natural laws, truths, principals, tradition and precedent, as well as to have the qualities of perseverance, determination to achieve, and enthusiasm in study and depiction. There a freedom and originality within the flexibility of the principals. One path leading to individual artistic expression includes the employment of individuality in thought, a respect for nature, and established truths and principals. Unity is made possible by an observance of principals that create it, thus a knowledge of fundamentals is key. 'Most of the problems in painting can be solved and originality achieved when we have a broad knowledge and respect for the purpose and importance of principals.' (p. 137)

'Whenever we see a fine painting we thoroughly appreciate the accomplishment of the artist. We admire his wisdom in selection and concept; his skill and ingenuity in execution. We know that genius, ability, perseverance and determination have contributed toward his artistic success - that he only succeeded by and endless study of fundamentals and by continually staying with each problem until it was mastered.' (p. 137)

Learning to coordinate and balance head knowledge with practical physical and intuitive knowledge takes manual practice and application. 'The first and last important matter in the study and practice of art is knowledge.' (p. 139)

3. Addenda

Evelyn Payne Hatcher writes of her parents: '...it was the process, the learning, even the struggle that was to them more important than the product.' (p. 142) Payne considered color studies made in the field to be for personal use only, he never signed or sold them as a rule. Two things were observed by Payne's sketches: they were either a study of forms, or of how to make pleasing compositional arrangements. Payne kept a small notebook in his kit as well as in his pocket along with a 6B pencil.

'Plein aire painters seldom paint larger works in the field, because the light often changes too rapidly. Sometimes as in early morning and near sundown, very rapidly indeed.' (p. 144) Some suggest that Payne's oil sketches were completed in less than half an hour. When Payne mentioned wisdom in the development of knowledge in this book, he most likely often means the practical and physical knowledge learned through experience with painting and sketching, not just head knowledge and study of books. '[Payne] planned compositions with pencil drawings and so was able to paint rapidly at the easel without laboring over layout.' (p. 146) 'Both [Evelyn's] parents insisted that practice in drawing from nature teaches one to really see, which is rewarding in itself.' (p. 146)

When Payne worked he often employed the following procedure:

1. Once he decided on the main subjects, the then tried out various compositions. In the field Payne would sometimes use a viewfinder (a rectangle cut out of cardboard) to help visualize the composition.

2. Next (whether executed in the field or the studio), 'was to draw the scene on canvas with charcoal, sometimes sketchy and sometimes in detail, depending on the subject, with indications of darker areas.' (p. 147)

3. Then he '...establish[ed] the pattern of darks and lights (values) by painting a wash or stain (often thin red ochre) over the dark or shadowed areas.' (p. 149)

4. Next, 'working all over the canvas, he used thin paint to establish the color scheme.' (p. 149)

5. '...thicker pigment was applied to the dark areas in hues that would be appropriate for the shadows...' (p. 149)

6. Applying heavier paint, he gave attention to the solidity of forms, 'modeling[.]' He worked to some extent from dark to light, as in traditional oil painting, but also tended to work all over the canvas to maintain the relationships between dark and light, warm and cool, in accordance with the color scheme he had in mind, leaving only the highlights for last.' (p. 149)

He worked in a similar manner with color studies in tempera, the differences being he started with a wash of color (or colored paper) and dabbed the paint on, leaving the background showing in some areas to produce vibrance. Payne laid out the darks and lights in a composition as he was drawing it, and thought first this way, beginners typically think in terms of local color first. A dividing of the picture plane in thirds is also a pleasing composition where focal points rest on the devision lines. 'The underlying principal of [Payne's] approach to color, and to art in general, is the balance of vitality (contrast and opposition) with harmony.' (p. 154) A principal which was discussed in the latter half of Chapter 2.

In the color section, Evelyn goes into detail explaining basic color theory, as well as giving a few examples of practical methods of execution for learning it such as a times table of paint mixing, and the 'soup' method.